Dementia Risk Reduction – Is it all in your head?

- Amanda Carapellucci

- Mar 9, 2021

- 8 min read

As discussed in a previous blogpost, the determinants of health have far reaching implications on our health. It is also recognized that there are various levels of influence that impact these determinants and, in turn, our overall health (Paskett et al., 2016, p. 1430). Multi-level health models address the fact that in order to make effective change, action is required within multiple levels of influence. A variety of multi-level health models exist, each conceptualizing the complex interactions between a person or population’s health, the determinants of health, and the varying levels of influence, in its own unique way. For this blog post, I have chosen to focus on the Population Health Promotion (PHP) model. The PHP model draws on the strengths of both population health and health promotion and allows you to create a “comprehensive set of action strategies” by exploring health determinants, and their various levels of influence (Hamilton & Bhatti, 1996). The PHP model includes action strategies across the following levels of influence: society, government policy, communities, family and the individual. I will demonstrate how this model can be used by applying it to dementia. Although there is no cure for dementia, we now know that there are at least 12 modifiable risk factors (Livingston et al., 2020). As I will go on to explain in more detail, hearing loss is the most influential of these risk factors, so I will be applying the PHP model to create risk reduction strategies for hearing loss in Canada.

POPULATION HEALTH PROMOTION MODEL

Population Health Promotion (PHP) is a multi-level health model grounded in the ideas of both population health and health promotion (Hamilton & Bhatti, 1996). The population health influence requires us to examine the full spectrum of the determinants of health, while the health promotion side is reflected by the action strategies. The model incorporates foundational public health documents that guide both its strategy and implementation, as highlighted in Figure 1. The PHP model requires you to answer 3 questions to begin to develop actionable health strategies:

In addition, evidence-based decision making must be used to guide all actions and initiatives. Decisions must be made based on research studies, experiential knowledge, and evaluation studies, and the decision-making process “must be made explicit” (Hamilton & Bhatti, 1996). A model showing all possible options is visually represented in Figure 2:

Figure 2 (Hamilton & Bhatti, 1996)

DEMENTIA & ITS RISK FACTORS

Dementia is defined as “a set of symptoms and signs associated with progressive deterioration of cognitive functions that affects daily activities” (CIHI, n.d.). The video below from Alzheimer’s Research UK explains the disease, and states that it is not a normal part of ageing (Alzheimer’s Research UK, 2016):

Globally, around 50 million people live with dementia and an additional 10 million new cases are added yearly (WHO, 2020). Dementia is “one of the major causes of disability and dependency among older people worldwide” and it has “physical, psychological, social and economic impacts” (WHO, 2020). Data from the CIHI tells us that as of 2013-2014 in Canada (CIHI, n.d.):

More than 402,000 seniors (7.1%) were living with dementia (increase of 83% from 2002-2013)

76,000 people are newly diagnosed each year

As Canada’s population ages, the numbers are only expected to increase.

Health care system costs were 5.5 times higher for people living with dementia

There is no cure for dementia, but there are modifiable risk factors.

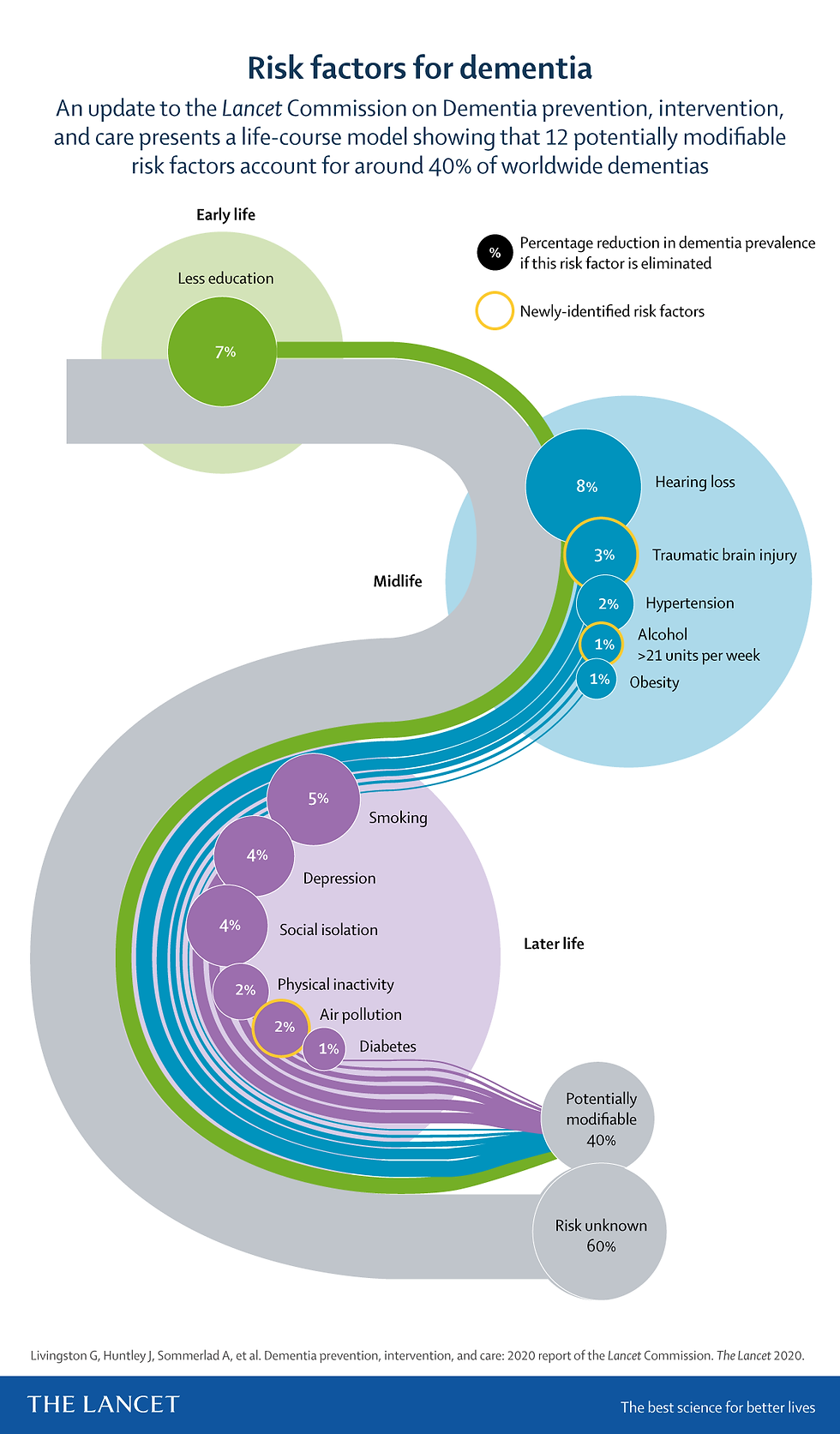

A 2020 commission on dementia prevention, intervention and care reports that there are 12 modifiable risk factors which account for 40% of worldwide dementias (Livingston et al., 2020). This means we could theoretically prevent or delay 40% of dementia cases worldwide by targeting these factors. Figure 3 illustrates these risk factors using a life-course model. I have chosen to explore how the PHP model can be used to address the most influential of the known modifiable risk factors: hearing loss.

Figure 3 (Livingston et al., 2020)

HEARING LOSS RISK REDUCTION STRATEGY

As noted in the infographic above, hearing loss accounts for 8% of the total 40% preventable dementia cases worldwide. Research shows that dementia risk increases with each 10 dB of worsening hearing loss (Livingston et al., 2020). How can we apply the PHP model to this health issue?

1. ON WHAT SHOULD WE TAKE ACTION?

All the determinants of health from the PHP model have the ability to affect hearing loss.

2. HOW SHOULD WE TAKE ACTION?

I have selected 4 of the 5 action strategies from the PHP model, detailed below:

a. Build Healthy Public Policy:

Implement hearing loss screening programs. In Canada, there are an estimated 74% of people aged 40-79 that have at least mild hearing loss (Statistics Canada, 2019). In contrast, self-reported numbers of hearing impairment in the same age group come only to 6%! This suggests that people are largely unaware of their hearing loss and that proactive screening initiatives need to be implemented.

Make hearing aids accessible to all Canadians as part of universal health coverage. The incidence of dementia is higher in people aged 65 years of older who report hearing problems, except for those who use hearing aids (Livingston et al., 2020). The price for hearing aids in Canada ranges from $995 to $4000 per ear (ARTA, 2020). Some provinces, such as Alberta, do supplement the cost of hearing aids for select eligible groups (Government of Alberta, n.d.). Overall, there is still work to be done to ensure that all Canadians have equitable access, regardless of their socio-economic status.

Implement legislation to regulate recreational noise exposure. Most countries currently have no legislation to control recreational noise exposure (WHO, 2015). In Canada, noise regulations are governed at the federal and provincial level, and additionally by by-laws at the municipal level. At the federal and provincial level, Canada currently has no regulations regarding recreational noise exposure (HGC Engineering Acoustical Consultants, n.d.).

Implement legislation that requires personal audio devices to include a customizable maximum volume limit (WHO, 2015). Although some manufacturers of audio devices have developed software to this capability, it should become a standard requirement.

Support the roll out of preventative campaigns. Targeted prevention campaigns that make good use of social media platforms can be used to educate children and parents about the consequences of hearing loss (WHO, 2015).

b. Create Supportive Environments

Below are a few environmental factors that lead to hearing loss:

Due to young people using earbuds at high volumes to listen to music, it is estimated that over 1 billion young people worldwide are at risk of developing permanent hearing loss (Chadha et al., 2018, p. 146)

Children may unknowingly be exposed to loud noises, at home or in their communities (WHO, 2015).

Loud work environments, and exposure to solvents (WHO, 2015).

Loud recreational activities, such as concerts, festivals, and parties (WHO, 2015).

Developing supportive environments can lead to better health outcomes which, in turn, can prevent or delay hearing loss:

Families/Parents need education on the factors causing hearing loss so they can play an active role in teaching their children healthy habits (WHO, 2015).

Teachers need to be provided with the tools they need to educate their students (WHO, 2015).

Physicians can educate and counsel their patients – especially adolescents – about risks and promote prevention (WHO, 2015).

Employers need to provide appropriate personal safety equipment to their employees if frequently exposed to loud noises or solvents (WHO, 2015).

Recreational venues where noise levels are high may consider supplying customers with free earplugs (WHO, 2015).

Communities can act on local issues that may impact hearing health.

c. Develop Personal Skills

All Canadians can benefit from developing personal skills that allow them to live healthier lifestyles and control their risks. Canadians need to be health-literate and have access to up-to-date information and education on preventing hearing loss (WHO, n.d.). They also need to be educated regarding the consequences of hearing loss. Providing people with the information they need to make their own decisions allows them to feel that they have more control over their health and future health outcomes (WHO, n.d.). Development of personal skills needs to happen at home, at school, at work, and within the community.

d. Reorient Health Services

There is an urgent need to refocus health services and spending on upstream, preventative action rather than reactionary treatment and management. In terms of hearing loss, we need to ensure that:

The health care system is equipped for early screening and detection of hearing loss (WHO, 2017). This includes:

- Appropriate and adequate screening instruments are available.

- Training and education for physicians and care teams regarding hearing loss screening, treatment and follow up care.

- Funding is available for regular check-ups, especially in high-risk populations.

3. WITH WHOM SHOULD WE ACT?

As we have seen through the detailed action strategies above, all 5 levels of influence play an role in a successful risk reduction plan for hearing loss: Society, Sector/System, Community, Family, and Individual.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

These action strategies are only a glimpse into what could be done to prevent hearing loss. Further research is warranted to determine whether disparities exist within geographical, racial, or socio-economic groups – as is often the case. Although the PHP model does not provide a hierarchy of levels of influence, it is easy to see from the action strategies that change is needed from the top down: Society > Sector/System > Community > Family > Individual. This ensures that when it is time for an individual to act, all of the supports and services required for them to make healthy choices are already in place. Working through the application of a multi-level model of health on a real-world issue truly makes you realize how inextricably intertwined our lived experience of health is from the determinants of health. Furthermore, we can clearly see how the determinants of health fall under multiple levels of influence, and how important it is for these levels to proactively work together achieve better health outcomes.

References:

Alzheimer’s Research UK. (2016, October 13). What is dementia? Alzheimer’s Research UK [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HobxLbPhrMc

ARTA. (2020, August 4). How much do hearing aids cost in Canada? The Alberta Retired Teachers’ Association. https://www.arta.net/news-events/wellness-tips/how-much-do-hearing-aids-cost-in-canada/#:%7E:text=Hearing%20aid%20prices%20range%20from,of%20hearing%20loss%20and%20lifestyle

Chadha, S., Cieza, A., & Krug, E. (2018). Global hearing health: future directions. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 96(3), 146. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.18.209767

CIHI. (n.d.). How dementia impacts Canadians | CIHI. Cihi.Ca. Retrieved February 19, 2021, from https://www.cihi.ca/en/dementia-in-canada/how-dementia-impacts-canadians

Government of Alberta. (n.d.). AADL – Benefits covered. Alberta.Ca. https://www.alberta.ca/aadl-benefits-covered.aspx

HGC Engineering Acoustical Consultants. (n.d.). Canadian Noise Regulations & Bylaws. Noise Ordinances. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://noise-ordinances.com/canadian-noise-regulations-and-bylaws/

Hamilton, N., & Bhatti, T. (1996, February). Population Health Promotion: An Integrated Model of Population Health and Health Promotion. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/population-health-promotion-integrated-model-population-health-health-promotion.html

Livingston, G., Huntley, J., Sommerlad, A., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S., Brayne, C., Burns, A., Cohen-Mansfield, J., Cooper, C., Costafreda, S. G., Dias, A., Fox, N., Gitlin, L. N., Howard, R., Kales, H. C., Kivimäki, M., Larson, E. B., Ogunniyi, A., … Mukadam, N. (2020). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 396(10248), 413–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30367-6

Paskett, E., Thompson, B., Ammerman, A. S., Ortega, A. N., Marsteller, J., & Richardson, D. J. (2016). Multilevel Interventions To Address Health Disparities Show Promise In Improving Population Health. Health Affairs, 35(8), 1429–1434. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1360

Statistics Canada. (2019, August 21). Unperceived hearing loss among Canadians aged 40 to 79. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2019008/article/00002-eng.htm

Strategies for Population Health: Investing in the Health of Canadians. (1994). Retrieved from: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/H88-3-30-2001/pdfs/other/strat_e.pdf

WHO. (n.d.). Health Promotion - Actions. Retrieved March 8, 2021, from https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/enhanced-wellbeing/first-global-conference/actions

WHO. (1986). Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/129532/Ottawa_Charter.pdf

WHO. (2015). Hearing loss due to recreational exposure to loud sounds - A review (No. 9789241508513). World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/154589/9789241508513_eng.pdf?sequence=1

WHO. (2017, May). Prevention of Deafness and Hearing Loss (WHA70.13). https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA70/A70_R13-en.pdf

WHO. (2020, September 21). Dementia. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

Comments